Who is a manager? Why do we need one? In the modern world of agile teams is a manager not superfluous? What does he do actually?

These are often questions I faced especially when I was talking to engineers in a start-up that we may have acquired. Typically, they were smart, self-motivated and did not care much for what they understood as a manager. They could easily understand the value of a technical lead, the value of a lead architect, but not that of a manager. And here they were, coming into a larger organization typically classically organized into a few management layers, and wondering why does this all make sense?

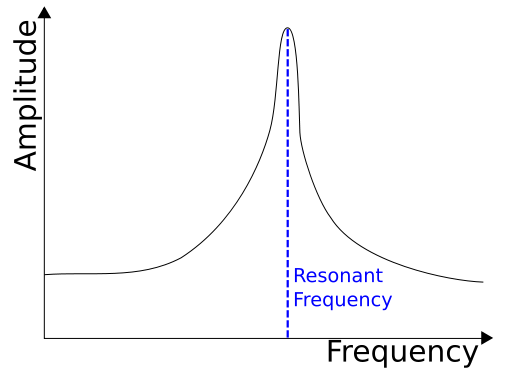

I have taken the help of physical principles to explain the value of a manager and it has worked more often than not. Just like each particle has a potential energy and natural frequency so does each individual working in a team. If a group of nearby particles vibrate in a matching frequency they cause a phenomenon called resonance. At resonance, the collective amplitude of the particles, an indicator of energy, is more than a simple summation of their energies. On the other hand, if the same group of particles vibrate in frequencies that do not match they may cause dissonance. At dissonance, the overall energy is less than a simple summation of their energies.

A good manager must be a synthesizer that causes resonance in a team. A good manager uses a number of techniques to harness the individual capabilities in the team members, align them, focus them on a clear goal, and thereby makes them collectively more effective than they individually have been by mere association. Thus, a good manager will take a team of five and make them appear as a team of eight. Thereby, in terms of productivity he would have paid three times his own overhead.

So practically speaking, how does a good manager typically achieve the above? The techniques could be various and in creative combinations. The first principle however, is to align the team in terms of clear goals and direction. Typically, he would establish meaning of shared success in terms of short term goals in the context of a long term direction. He would then deeply understand the inherent strength of each team member and assign individual objectives leveraging that strength. He would then align the objectives such that they come together perfectly to achieve the team goal. He would institute just the correct amount of checkpoints to tune the progress of each individual toward his objective and ensure the objectives are almost continuously aligned in direction and speed with the goal. A good manager sometimes will act as a domain expert or technical lead and coach in a specific matter; sometimes he will act as an informed decision maker when there are divergent choices; sometimes he will act as a social lubricant to remove friction between team members; sometimes he will help handle exceptions when a team member is temporarily handicapped for example due to a family situation or sickness.

A bad manager is a damper that causes dissonance in a team. He would typically not understand individual capabilities to sufficient depth; he would not align individuals in the team toward a clear goal and explain each person’s role in achieving the goal; he would sometimes interfere in natural progress of an individual by “checking in” too often; he will give conflicting messages over time and effectively confuse the whole team. A bad manager will take a team of five and make it look like a team of three. It would be better if he were not there at all.

Typically a bad manager displays well known symptoms. It would often start with the inability to explain to the team what the longer term direction and short term goals are. Worse yet, often he will create short term goals that appear important and pressing and drive the team toward those goals but they actually don’t matter or are not the right goals. This way he is dissipating the team’s energy without meaningful progress. He would often call regular meetings without clear agendas and objectives and the meetings would become a pro-forma waste of time. He would institute a pure overhead process like documenting time spent on various activities. He may be as worse as creating rift within the team by consistently favoring or supporting someone’s opinions over another without factual basis because he happens to like one over the other. He will typically not consult team members before making a hiring decision about a new person coming into the team. Sometimes he may be a domain expert and thus he will consistently push his views over others thereby depleting team morale and individual growth. In combination, all of his traits and activities will dissipate the natural energy of the team, cause friction hence loss of energy, and thus making the team much less effective than they would have been without a manager.

The good news is that in a well-managed company, it is easy to tell a good manager from a bad manager. Observing some simple traits, senior management can call this out. A team managed by good manager will have little or no attrition; the team will consistently exceed expectations in the work they deliver; any open position in the team will be heavily targeted by internal employees; the team will appear engaged with senior management and ask inquisitive questions in round tables or in the coffee room regarding company strategy; team members will be regularly recruited by other managers for promotional opportunities; the team will successfully steer itself in any temporary absence of the manager.

A team managed by a bad manager typically will have noticeably higher attrition than an expected norm; they will struggle to fill open positions internally, and may even struggle to fill externally; the team will miss consistently on deliverables or produce low quality deliverables; the manager will often cite a poor performing employee for those outcomes; the team will sit quietly in senior management roundtables or ask questions that their direct manager should have answers for; the team members will never be sought after by other managers for internal promotions; the team will very drastically become unproductive in any temporary absence of the manager because the manager has not instilled in self-formation in the team that propels them forward.

Again, in a well-managed company one would expect bad managers will be detected easily and be asked to leave at least their management role.

Organizationally, it is more dangerous to have a zero-value manager. A zero-value manager is typically a passive person who does a reasonable pro-forma job in terms of job responsibilities but does not add any value or amplify the team’s energy. Neither does he noticeably reduce the team’s energy and cause visible challenges with attrition and deliverables. Here are some traits of a typical zero-value manager: he simply relays senior management messages down to his team typically in forwarded emails; he gathers team opinion in some matter and either averages the opinion or chooses a dominant opinion and passes it up without exercising any thought or judgment on his part. This is what is called a “message-passing” manager. He will typically take a set of “strategy” charts available in the company internal website and use it verbatim to explain strategy to his team without relating it to the team’s goals. He will regularly have one-on-ones with team members but they would be mostly about completion of tasks and set of next tasks. A zero-value manager will sometimes be needlessly affiliative in teams social interactions and strive to be popular among the team members. He will typically not challenge a poor performer but distribute the overflow work to other team members. He will try to give equal or average evaluations to team members and fail to differentiate. His team will typically do a good job of managing short term goals and deliverables but will rarely surpass or exceed expectations. His team will not see much attrition but will not attract external team members. Typically his team members will have high tenure in the team and be in a satisfied state regarding their careers. They may be mildly dissatisfied about a few things like compensation, facilities, etc. but not enough to do anything about it. In all respects, the manager and the team will be average.

Why is it more dangerous to have a zero-value manager than a bad manager? Zero-value managers create average teams that stay below the radar and get by internally. In a large company it is possible for these teams to be undetected for a while and grow like mushrooms. If a division has twenty-five percent such zero value managers and average teams, no one pulls an alarm chain. The division falls behind competition, does not innovate, and stays in a long term state of mediocrity. In some sense the “undetected average” is worse than the “detectable and correctable worse”. Zero-value managers and average teams cause a silent form of organizational cancer to the long term detriment of the organization. Senior management should be sensitized to this and must create a culture of challenge and innovation for every team such that there is no tolerance for average.

A bad or a zero-value manager is not necessarily a bad or zero-value employee. It is quite common that a domain expert and an otherwise talented person is promoted to management and he is not simply either equipped, or truly interested, or has the innate talent to manage anything other than his own duties and goals. Sometimes it is best for the organization to ask the employee to return to be a valuable individual contributor– he may actually be happier and very productive. Sometimes, all that is missing is a good amount of techniques and training and the person will be an excellent manager. Good training is critically important especially at the start of a management career.

Good managers are the best; bad managers are not ideal; zero-value managers are the absolute worst.